Many scholars have exposed the importance of urban agriculture (UA) for women in developing countries, especially because UA empowers them. However we don’t find much information in the literature about women involved in UA in developed countries. One phenomenon that called my attention during this course in Montreal as well as in Portland was that farmers in rural areas are mainly males, whereas women seem to be taking the lead in urban settings.

Entrepreneurship was well represented by women in both Montreal and Portland. A good example is De Blanc de Gris, a company located in Mercier – Hochelaga-Maisonneuve in Montreal, which produces fresh oyster mushrooms for local restaurants and markets. Dominique Lynch-Gauthier et Lysiane Roy Maheu started the business with the support of their families and public grants. It took one and a half years of design, financing and looking for the right place to install the facilities to start producing mushrooms. These are grown on organic residues produced in the neighborhood, such as wood chips, beer brewer’s dregs, and coffee grounds. Overall the company consumes 50 tons of the neighborhood waste per year. Residues leftover after the mushrooms are harvested are picked up by neighbours mainly to be used as compost for their gardens. What strikes me the most about Dominique and Lysiane is that they made this smart idea real…. We can feel there was and there is a lot of work behind the gorgeous oyster mushrooms. They are delicious with fried onions, garlic, olive oil and cilantro.

During our week in Portland we got to visit a couple of commercial urban farms that were created and managed by women: The Side Yard Farm and Kitchen, already described by Gwyneth in her blog of September 7th, and The Blue House Greenhouse farm, located in North Williams and North Cook. The last was started in 2010 by Amanda Morse, which holds a degree in Sustainable Food Systems and has a background in food production and education. She works on average 25 to 30 hrs per week with three more people to grow food during almost the whole year. Even when volunteers help her with the farm (in exchange of produce), she cannot live entirely from it and also has a part time job. The main challenges she faces are water supply and pressure to build in the land she occupies. Actually, the farm is surrounded by two buildings in ongoing construction. Amanda knows that her farm is at risk of being shut down because of construction, but she enjoys farming in the present moment. Despite knowing that her farm could potentially contribute to gentrification, she believes in what her work brings to the community (low income), green space, local and healthy food and a place for community building.

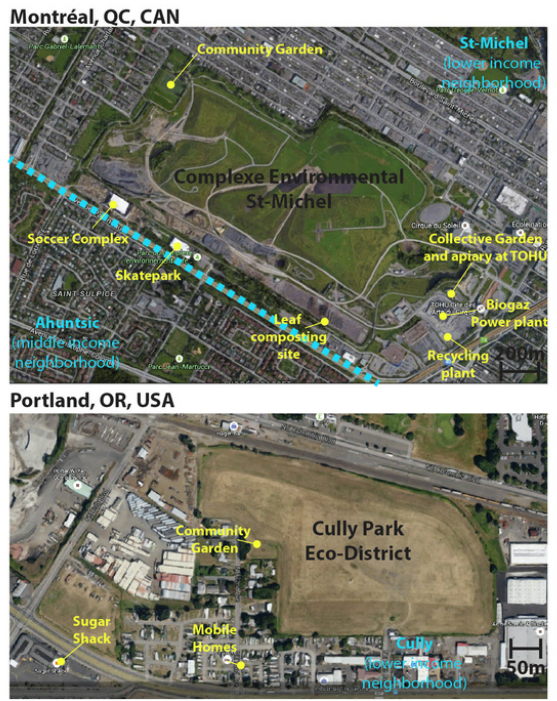

Gardening is important for many low income women and their families in Portland. Growing Gardens is a non-profit organization, whose mission is to support low income households to grow produce in available spaces (back and front yards, side yards, balconies, etc.). The organization is helping Mexican women, technically and financially, to grow a portion of their food in the Sequoia Square apartment’s common patio. The apartments are part of a low income housing project. Most of the women here are at home with their children and don’t speak English. Therefore they are isolated from the rest of the community. The gardens help them to socialize with other Spanish speaking mums and remind them about their cultural background. These women specially value gardening with their children, so they can offer them a bit of tradition from Mexico. Similarly, NE 72nd Community Garden, in Cully neighborhood, offers space to grow food to many immigrants. I spoke with two Mexican women who garden here. They cultivate many of the traditional plants they used to eat in Mexico and the produce they get is enough to feed their families so they don’t need to buy these products in the market. Husbands don’t usually garden with their family because they have full time jobs, but they build the fences for the plots. Racial discrimination seems to be intense for Mexicans according to the gardeners, and the time they spend taking care of their plots helps them to get going with life in Portland.

Paulina is a single mother and volunteers to coordinate the garden of the King Pre School Garden in the heart of NE Portland. She explained that 80% of the children assisting the school come from low income families. Paulina believes that education is important in supporting the community to adopt better healthy eating habits. So far, since she started in March of this year, children have participated actively and enthusiastically in the garden. However, much more support and participation is needed, especially from the school, to get the most of the garden. Being a single mom, volunteering to educate children and their families about gardening healthy food makes her a superhero!

Paula Cabrera

RSS Feed

RSS Feed