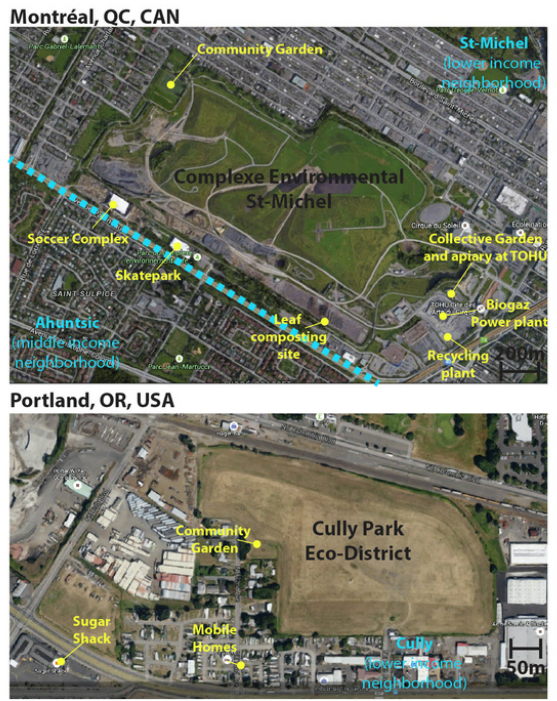

This is a story that likely happened in several places around the world, but the specific settings of this chapter are in Portland (PDX, OR, USA) and Montreal (MTL, QC, Canada). Both sites have a lot in common. They are nested within low-income neighborhoods (Cully and Saint-Michel) where reside people from various "etnic origins", according to the french-canadian ethical denomination, or the equivalent "people-of-color", as per the american standard nomenclature. From the early (MTL) or mid (PDX) 20th century to the 1980s, the two sites on opposing end of the continent were mined, amongst other things, for gravel. The MTL site was famous for dangerous operations and poorly calibrated explosive projected massive rocks in the homes of residents from the adjacent middle income neighbourhood (yes, there is still a middle class in Canada). Once the exploitation was over, a deep scar (15m in PDX and 70m in MTL) at the surface of the earth needed healing. Filling the hole with rubbish appeared as a brilliant solution. MTL welcomed household waste for 33 years (1967-2000), until limiting accepted waste to construction, renovation and demolition (CRD) debris in 2009 to minimize neighborhood nuisance (food waste generates more offensive odors and attracts rodents and seagulls) and prepare for an eventual site closure (capping completed in 2013)[i]. On the other hand, PDX solely burrowed CRD waste for the 10 year the landfill was in operation.

[i] http://tohu.ca/fr/cesm/historique/

[i] http://tohu.ca/fr/cesm/historique/

To protect groundwaters from heavy metal, nutrients and other organic pollutants leachate, the MTL site engineers relied on earth's secular natural protection, a thick mantle of clay at the bottom of the pit through which water infiltrates infinitely slowly. Leachate was collected and filtered at extensive costs, but this did not prevent a toxic plume formation in the groundwaters. The PDX site innovated, it was was the first in the state to use a special geomembrane to prevent this problem, though the long term impermeability of such membranes is yet unknown.

To protect earth's atmosphere from greenhouse gas emissions originating from anaerobic organic waste decomposition, the two sites relied on the same gas capture principle. However, poor conception of the capture system at PDX led to methane accumulation in the ground, with leaks of this potentially explosive gas all the way to neighbors’ basements. Hence, a renovation of this system was tackled by the federal government. In MTL too methane leaks were recorded close to nearby businesses. There, a system was conceived to capture the gases and supply a 25 MW power plant, the 3rd most important project of this type in the world[i], able to energize 15 000 homes[ii]. Unfortunately, decreasing emissions capture did not sustain the power plant which was shutdown in 2014 and revamped to improve efficiency[iii].

[i] http://www.biothermica.com/sites/biothermica.com/files/Chauffage%20urbain%20par%20Gazmont.pdf

[ii] http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_dad=portal&_pageid=7237,75372064&_schema=PORTAL

[iii] http://journalmetro.com/actualites/montreal/469715/gazmont-croit-toujours-aux-dechets-montrealais/

[i] http://www.biothermica.com/sites/biothermica.com/files/Chauffage%20urbain%20par%20Gazmont.pdf

[ii] http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_dad=portal&_pageid=7237,75372064&_schema=PORTAL

[iii] http://journalmetro.com/actualites/montreal/469715/gazmont-croit-toujours-aux-dechets-montrealais/

The future appears brighter for both sites where rehabilitation plans including eco-districts and large parks unfold. In MTL, the city planned a 192 ha park surrounded by businesses within an Environmental Complex. There ecological infrastructures (LED certified circus headquarters, theatre and indoor soccer field) are co-developped along with policies to favor hiring of the low-income neighbors. To concentrate sustainable waste management on site (where a recycling facility and leaf composting sites are already located), the city proposed a large-scale biomethanisation plant. This led to a revolt of the community who felt they had already suffered enough because of the site's history. The administration heard their appeal and proposed a remote site. This nevertheless collaterally led to wasted tax-payers money and delays for the opening of the much needed facility with the 2020 organic waste landfill ban fast approaching[i]. Urban agriculture programs extended beyond the existing community garden with vegetable growing and apiary projects (TOHU). Native people were honorifically included in the design of gas capture pipes which will be covered with domes similar to traditional sweat lodges, where indigenous vines will grow. Neighborhood resident committee keeps a tab as planning and construction unfolds, but the community involvement in MTL appears embryonic compared to the PDX process.

[i] http://www.ledevoir.com/politique/montreal/386227/le-centre-de-compostage-est-menace

[i] http://www.ledevoir.com/politique/montreal/386227/le-centre-de-compostage-est-menace

Entrance to the Community garden is behind a trailer park on NE 72st street (left). The Cully neighborhood is poor and was home to criminal activities (i.e. at the Sugar Shack) until a group of citizens and not-for-profit organizations decided to reclaim their neighborhood (right). Photos: Louise Hénault-Ethier.

In PDX, the community initially had to fight to reclaim the Superfund site which suffered from lack of municipal leadership. The "Let us build Cully park" movement was born with the intent of opening a 25 acre (10 ha) park by 2017[i]. But instead of having a limited power consultative resident committee, an innovative approach to participatory planning unfolded. Residents were paid to learn about site contamination, planned a sampling with the help of accredited professionals, and acted as ambassadors in their community to confirm the safety of the site. Students were involved in the planning of the community garden which had, to the great delight of one of them, to be built on uneven terrain. Native urban communities secured an inter-tribal gathering garden where the generalized prohibition on picking natural flora was alleviated for cultural purposes. All of these efforts were integrated in a greater plan to build wealth in this low-income community eco-district taking concrete measures to avoid displacement and gentrification.

[i] http://letusbuildcullypark.org/

[i] http://letusbuildcullypark.org/

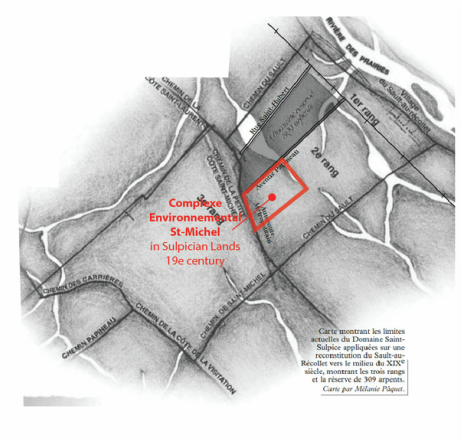

This comparative history shows that several approaches are possible to rehabilitate environmentally and socially damaged urban neighborhoods which lived through mining, landfilling and social inequity. The MTL approach appears more institutionalized, whereas the PDX approach is more grass roots. However, both projects eventually met through the development of urban agriculture, a rising trend addressing environmental and social sustainability. It’s interesting to see how the loop was closed, as the MTL site was cultivated to feed the growing city in the 18th century.

By Louise Hénault-Ethier

RSS Feed

RSS Feed